Yesterday the wind blew stuff all around our yard and knocked down tree branches around the neighborhood. This morning I took this photo of the smoke coming from the Eton fire in the east:

To the north of us is the Hurst fire, to the south is the Sunset fire and you’ve probably seen images from the Palisades fire way to the west. I know some people who have lost their homes. A bunch of events, including school, have been canceled “out of an abundance of caution”. Our neighbor across the street lost power and is using our outlets to charge stuff. We lost internet for a bit this morning. This is fine.

It’s a predictable pattern in the chaparral:

- Wet years mean extra growth in the hills.[1]

- Dry summers turn vegetation into extra fuel in the hills.

- Santa Ana winds blow small fires down canyons.

- If there’s heavy rain in the spring, we’ll see mudslides in the burned areas.

A study of charcoal deposits in Santa Barbara shows this pattern goes back hundreds of years. It predates climate change, fire suppression and concentrated human occupation. Every 20–30 years a site will have a large fire that clears out vegetation and starts a new cycle of growth.

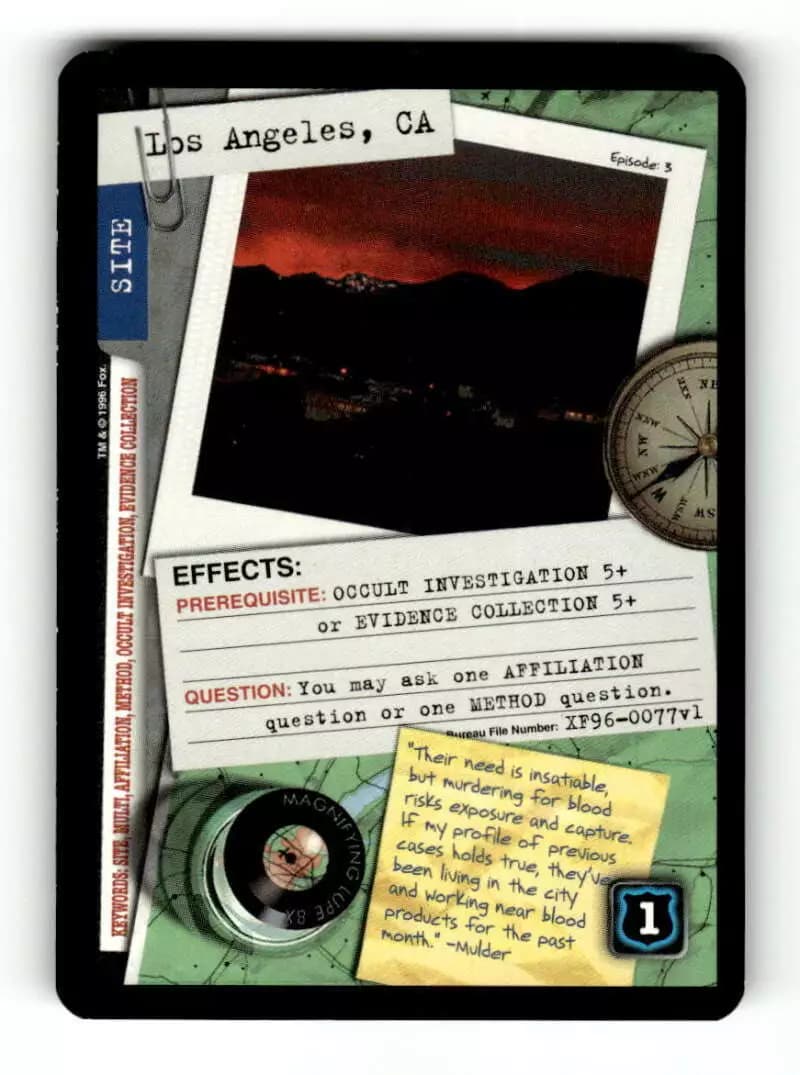

Shortly after I moved here in 1993, a series of wildfires created an eerie atmosphere that inspired an episode of the X-Files. While we usually think of California’s danger as earthquakes (such as the 1994 Northridge event), fire has been the cause of most of California’s disasters.

This isn’t to say we can’t learn from these fires:

- Maybe prescribe burns when the wind danger is lower to reduce the severity of fires after particularly wet years.

- It’s always a good idea to clear dry brush near homes.

- When it comes time to replace siding and roofs, opt for fire resistant materials.

Ultimately, however, fires seem to be part of the cost of living in this part of the world.

On the plus side: we aren’t in drought conditions. ↩︎